August 15, 2012 · 11:03 pm

Following on from the success of her debut novel, Debris, Jo Anderton‘s new book Suited has been released into the wilds. She’s dropped by today to talk about ‘the suit’ which inspired the book.

The story behind the suit

The first time Tanyana saw a debris collecting suit, she mistook it for jewellery. It was, after all, a thick silver bracelet, intricately inscribed with arcane symbols and glowing faintly. That was before one was forcefully drilled into her body, of course. Before she learned that there was much more to it than the bright silver bands — attached to her ankles, wrists, waist and neck — and that it went deep beneath her skin, bound to her nervous system and anchored in her bones.

The first time Tanyana saw a debris collecting suit, she mistook it for jewellery. It was, after all, a thick silver bracelet, intricately inscribed with arcane symbols and glowing faintly. That was before one was forcefully drilled into her body, of course. Before she learned that there was much more to it than the bright silver bands — attached to her ankles, wrists, waist and neck — and that it went deep beneath her skin, bound to her nervous system and anchored in her bones.

This debris collecting suit was the catalyst for everything that happened to Tanyana in Debris. And, as you might have guessed from the title and the cover image, it becomes even more important in book two, Suited.

So what is the suit? And what inspired it?

Tanyana’s world is full of pions — semi-sentient sub atomic particles that can be persuaded to rearrange matter. The better you are at directing them, the more powerful you can become. Before the accident that stripped Tanyana of her powers in the beginning of Debris, she was a highly skilled binder and architect, able to command vast numbers of pions. Everything in her world is built with these particles, from something as mundane as a sewerage system, to the might of the military machine. But all this power comes at a cost. Pion manipulation generates a waste product — debris. The more you manipulate, the more debris you create. And debris can be a serious problem, because it destabilises pion systems and can, if left unchecked, completely undo their bonds. For a city built on pions, debris is a real threat.

This is where the debris collectors come in. You see, most people in this world can see and manipulate pions, but they wouldn’t know debris was there if it was floating right in front of their noses (as it tends to do…) Only people who have lost their pion-sight, or were never born with it, can see debris. They are recruited by the government, fitted with suits, and sent out to collect it. Buried within the suits’ six bands is a strong but malleable metal that can expand, and morph into any shape. From delicate tweezers to great shovels or, should the need arise, a sharpened blade.

But Tanyana’s suit is different. From the start, it’s more than just a tool. It has a tendency to move on its own, protecting Tanyana, or reacting even before she has thought to do so. Not only can she use it to shape tools or weapons, but Tanyana’s suit can also spread far enough to wrap around her body, head to toe. In fact, it seems to prefer that. Sometimes it feels almost sentient. It tugs at her bones and thrills down her nerves and whispers to her, inside her. Wouldn’t it be easier to do what it says, and just give in to it’s… violence?

There are times when it’s hard to tell who’s in control: Tanyana, or her suit. And this struggle is what Suited is all about.

So what inspired it? There are a lot of anime influences in these books, and the suit is probably the strongest example. Let’s see… It’s a powerful metallic creature with a mind of its own. It tends to save Tanyana and scare her in equal measure, and its origins are shrouded in secrecy and possible-dodgyness. Well, that’s Neon Genesis Evangelion right there. But don’t worry, the suit isn’t Tanyana’s mother, I can promise you that! Also, this story has absolutely nothing to do with the Dead Sea Scrolls.

So what inspired it? There are a lot of anime influences in these books, and the suit is probably the strongest example. Let’s see… It’s a powerful metallic creature with a mind of its own. It tends to save Tanyana and scare her in equal measure, and its origins are shrouded in secrecy and possible-dodgyness. Well, that’s Neon Genesis Evangelion right there. But don’t worry, the suit isn’t Tanyana’s mother, I can promise you that! Also, this story has absolutely nothing to do with the Dead Sea Scrolls.

What about Full Metal Alchemist? Have you guys seen that? If you have, think about Edward’s metallic arm for a minute. The way he uses his alchemy to morph it into any shape, often a sword. Now that’s exactly what Tanyana’s doing with her suit — except she’s using neural connections and muscle memory, not alchemy. If you haven’t seen FMA — do so, now. New series, old series, I don’t care (I liked the old one. Yes, even the ending).

But, you know, I think there’s more to the suit than just anime. Not that there’s anything wrong with that — seriously, I’m the last person to demand deep and meaningful. Give me a good story first and foremost, the rest is just in the telling. Anyway (sorry, getting sidetracked) the suit is also the darkness inside us. It’s a rebellious body, a part that can’t be controlled, something foreign taking you over. It’s an inner violence begging to be let out, growing harder and harder to deny. And this, really, is the point of Suited. The suit, initially forced on Tanyana, is now well and truly a part of her. Through the course of Debris, she learned to control it, she found its limits and its strengths and pushed them as far as they would go. In Suited, the suit starts to push back. But, as I said, it’s a part of her now, inside and out, physically and mentally, and growing more so every day. How can Tanyana fight herself? Where’s the line between Tanyana and suit, and how long will that remain? Is it still her body, if the suit controls more and more of her? How important are our bodies to our sense of identity, and how much do we change when they do?

And hey, guess what, that’s very anime too. Couldn’t you say the same things about Evangelion, Full Metal Alchemist, Ghost in the Shell, and so many more? Maybe that’s because it’s a fundamental human conflict, made physical through the suit, or the Eva, or alchemy? And that’s why we love sci-fi, isn’t it? Because that’s what science fiction is for.

Jo has a copy of Suited to give-away. Here’s the question:

Pretend you’re at the end-game, it’s the ultimate fight with the ultimate big-bad, what would you take with you? From any book, game, movie or tv series. Do you like an old-school magical sword, or would you prefer a giant mecha? Lightsaber, or a summon? What’s the coolest weapon ever?

Filed under Australian Writers, Book Giveaway, creativity, Nourish the Writer, Resonance, SF Books, Writers and Redearch

Tagged as Angry Robot, Debris, Inspiration for Writing, Jo Anderton, science fiction, Suited

July 25, 2012 · 12:32 pm

I have been featuring fantastic female fantasy authors (see disclaimer) but this has morphed into interesting people in the speculative fiction world. Today I’ve invited the talented Lee Battersby to drop by.

Look out for the give-away at the end of the post.

Q: You’ve had over 70 short stories published, won the Aurealis Award, Australian Shadows Award (twice) and won an International Writers of the Future competition. Prime books published a collection of your short stories called Through Soft Air. Do you think the discipline of writing short fiction, helped hone your skill for novel writing?

I think my short story writing experience helped when it came to building scenes and establishing coherent lines of narrative, but I found the shift from writing the short to long form a bit dislocating in many ways. I’d probably become too entrenched in the short form way of thinking, and had to leave a lot of shorthand habits behind. It’s still a bit of a wrench to write long establishing scenes, for example, and I still absolutely hate writing long descriptions of landscape or setting—short story thinking demands I get to the bloody point now, dammit! One thing I do enjoy when writing novels is the opportunity to write increasingly complex streams of dialogue: I like the narrative cut and thrust of spoken wordplay, and the way you can reveal and hide information simultaneously. In short stories you use dialogue to reveal the narrative a little more quickly. In novels, you can be a bit richer.

I think my short story writing experience helped when it came to building scenes and establishing coherent lines of narrative, but I found the shift from writing the short to long form a bit dislocating in many ways. I’d probably become too entrenched in the short form way of thinking, and had to leave a lot of shorthand habits behind. It’s still a bit of a wrench to write long establishing scenes, for example, and I still absolutely hate writing long descriptions of landscape or setting—short story thinking demands I get to the bloody point now, dammit! One thing I do enjoy when writing novels is the opportunity to write increasingly complex streams of dialogue: I like the narrative cut and thrust of spoken wordplay, and the way you can reveal and hide information simultaneously. In short stories you use dialogue to reveal the narrative a little more quickly. In novels, you can be a bit richer.

I’ve written in a myriad of forms over the years: stage plays, TV scripts, stand-up comedy, poetry… each form comes with its own rules and ways to break them, and I think the more forms you work in, the better you’re able to adapt to new disciplines. The important thing is not to become hide-bound by one form. I’ve produced the best short stories of my career over the last couple of years, without a great deal of market impact, so I’m making the transition to novels at the right time. I could have done so a couple of years ago and been a bit further along in my career plans, perhaps, but the Angry Robot Open Door success came along at exactly the necessary moment.

Q: You wrote a post for the ROR blog where you described the rollercoaster of submitting to the Angry Robot Open Submission Month. (994 manuscripts). And now your book The Corpse Rat King has been published. (Mega congratulations!) If you could go back and give yourself some advice when you submitted that manuscript, what would it be?

Not a single thing: the novel got through the process, it was picked up, I gots me an agent. I think it pretty much ticked all the boxes!

I was fortunate in that I submitted as a reasonably experienced author, so I knew not to hang about waiting for something to happen. I was already writing another novel—I had 52k of it under my belt before the contract was signed—and was working on a bunch of other stuff while I waited. So I was quite happy with the way the whole submission process panned out: I’d been a bit moribund beforehand but it revitalised me, and got me thinking of my career in different terms, which has been refreshing.

Q: The sequel to The Corpse Rat King, Marching Dead, is due out in 2013. Has it been a very different process writing a sequel, while editing the first book? And do you have an idea for a third book in the series?

It has been different, in that I’m working to a deadline, as well as not being in the position where I can make up characters and locations from scratch. In a sense I’m much less free than I was in writing the first volume. Characters are established, distances are established, locations and levels of technology are all established. I can’t just make stuff up as I go along, so if I’ve cocked something up in creating the first book then I have to work with it and make it acceptable. That said, of course, I’m able to allow my characters to grow to a much greater extent, so it’s a lot of fun answering questions that may have arisen in volume one. And there are a few revelations along the way, too: the advantage of not working to a plan is that I can be surprised by something that pops up unbidden in the first draft and then, by the time the final draft is finished, make it look like I intended that to happen all along .

It has been different, in that I’m working to a deadline, as well as not being in the position where I can make up characters and locations from scratch. In a sense I’m much less free than I was in writing the first volume. Characters are established, distances are established, locations and levels of technology are all established. I can’t just make stuff up as I go along, so if I’ve cocked something up in creating the first book then I have to work with it and make it acceptable. That said, of course, I’m able to allow my characters to grow to a much greater extent, so it’s a lot of fun answering questions that may have arisen in volume one. And there are a few revelations along the way, too: the advantage of not working to a plan is that I can be surprised by something that pops up unbidden in the first draft and then, by the time the final draft is finished, make it look like I intended that to happen all along .

I do have a story arc worked out for the 3rd book, just in case the first two do well and Angry Robot decide to commission a third. I know the beginning, and the end point, and the Great Big Decision ™ Marius will have to make in order to reach it. Any more than that will generally work itself out in the writing. But it would be fair to say that any shit my heroes managed to pour all over themselves in the first two books would be nothing when compared to volume three!

Q: You have tutored at Clarion South and you have an article on the Australian Horror Writers Association web site Industry Advice. The industry is changing so fast. Once it was the kiss of death to self-publish, now many authors are self-publishing their back lists. Do you find yourself scrambling to keep up?

I’m not a big fan of self-publishing new pieces: to my old-fashioned way of thinking it still carries the whiff of work not good enough to attract a more traditional publisher. However, I can understand why an author who has the time and energy to do so would want to release older pieces directly to the public without any intermediary: the work has already undergone a process of third-party quality control, the dialogue between author and reader can be made more immediate, and the cash flows more directly to the writer.

I’m not a big fan of self-publishing new pieces: to my old-fashioned way of thinking it still carries the whiff of work not good enough to attract a more traditional publisher. However, I can understand why an author who has the time and energy to do so would want to release older pieces directly to the public without any intermediary: the work has already undergone a process of third-party quality control, the dialogue between author and reader can be made more immediate, and the cash flows more directly to the writer.

I readily acknowledge that I’m a little bit behind the times in my thinking: I still adhere to a traditional publishing model for my work, and I’m comfortable with that. I see a number of authors putting their own work out via electronic self-publishing, and it seems to me a very labour intensive way to go about your business. But when it comes to the marketplace, authors have to understand that they are small business owners, and as a small business owner, you have to decide the best way to market your product and how much time you’re willing to spend in developing the means of production. My instinct has always been that I’m too time-poor to be an effective electronic self-pubber, so I’ve steered away from it: I’m not passionate about that process, I’m not an adherent of the delivery system (I don’t own an e-reader, I don’t plan to own one, etc.), and for me, what time I do have is better utilised in other ways. That’s no comment on those who do choose to go down that track, just a fairly honest assessment of where my own strengths and weaknesses lie.

Ultimately, the best delivery medium, and the way you promote and market yourself as an author, is decided by the overall goals you have for your career. Self-publishing doesn’t attract me because it doesn’t fit in with my strengths and it doesn’t align with the direction I want my career to take. I keep in touch with the discussions, because I think every writer should be at least passingly familiar with the trends and evolutions of their business environment. But my limited experience shows me two levels of work being pushed—electronic reprints of paper books, which any sensible author should be pursuing as a negotiable clause in their contracts anyway, and original e-only works: the literary equivalent of a straight-to-video release, with the accompanying wild variations in quality. And I’m not sure I’ve discovered an efficient-enough means of separating the wheat from the chaff to make jumping into that second category a time-effective way to spend my writing career.

There may come a time when I look at self-publishing my story backlist, but truth be told I’d be just as comfortable with a small press publisher swooping in and offering to do all the hard business stuff for me in return for a cut of the proceeds, or paying me a flat fee as per the traditional business model. That might mean a cut in my potential in-hand profit, but I make a good living so money’s not that much of an issue, and at the end of the day I like real, hold-‘em-in-your-hand dead tree books, so it’s a compromise I’m happy to make.

Q: Your wife is talented writer, Lyn Battersby. With two creative people, who happen to be creative in the same medium in the same house, do you find this is a blessing or a curse? Do you read each other’s work and give feedback? Or do you find you can’t bear to do this? Have you considered collaborating? (eg. Written by L & L Battersby).

Lyn and Lee (courtesy Cat Sparks)

Lyn and I have collaborated on one story: a post-alien invasion tale called ‘C’ that, for a number of reasons, never really satisfied either of us so never saw the light of day. We’re both gearing up to work more as full-time novelists now, so the chances of collaboration on a fiction project aren’t high. Lyn writes much more elegant and subtle prose than I do, and her subject matter tends to be far more intimate, so I think there’s probably a clash in approach that doesn’t benefit our respective strengths. Once she gets the recognition her work deserves she’s going to become far too rich and famous to suffer having me riding her coat-tails, anyway…

But it’s definitely more a blessing than a curse to be married to someone with the same career goals and aspirations, simply because of the level of understanding. One of us can call ‘writing night’ at any time and there’s no argument, and when we talk it’s in the same language. We did read each other’s work a lot more when we were less experienced, mainly, I think, as a form of reinforcement that what we were doing made sense to someone else. Now we’re fairly confident in our own abilities we tend to read each other for pleasure, and Lyn doesn’t read my long work—she wants to wait for it to come out in proper novel format. But we’re always on hand to offer instant advice or an opinion, and as we generally can’t stop talking about current projects we usually have a pretty good idea what each other is working on, where we’re at with it, where it’s going, how rich it’s going to make us… just normal, everyday, married person conversations .

Q: I was prompted to start this series of interviews because there seems to be a perception in the US and the UK that fantasy is a bit of a boy’s club. Do you think there’s a difference in the way males and females write fantasy?

It’s a gross generalization to split a literary genre along gender lines, but I think you could argue that there are differences in the way males and females perceive fantasy, inasmuch as we seem to fantasize for different reasons. We’re a fairly small outpost in Australia, and I think it’s probably a bit easier to do a head-count than in the larger markets, so we’ve got a pretty good idea of our gender mix, which is increasingly healthy if not yet equitable. It helps to have good, strong publishers who understand the need for variation in theme and approach: in particular, Twelfth Planet Press and Fablecroft Publishing are two houses that are helmed by smart, high-quality editor/publishers who strive to promote a more literate, intelligent type of fantasy, which is the sort of environment where subtler forms of writing can thrive.

I think the male/female style argument is a somewhat simplistic one, and I’d like to think that as an industry we might have become a little more sophisticated than that, at least here in Australia, because I can see the Australian SF small press working hard to provide opportunities based on idea and theme rather than gender alignment, but as I said, it’s easier to look at the demographic in its entirety here, and also easy to view things from the perspective of a white middle-class male with few barriers to his career. My wife, who writes beautifully subtle and elegant works that often don’t pass through the quick-read filter, might gently intimate that I’m talking shit.

Q: Following on from that, does the gender of the writer change your expectations when you pick up their book?

Q: Following on from that, does the gender of the writer change your expectations when you pick up their book?

Not a bit. I’m utterly disinterested in the gender of the author when I pick up a book. Gender is just a description of where your dangly bits dangle from. It’s not an expression of sexual orientation, political affiliation, socio-economic outlook, or any of the umpty million psychological, societal and environmental factors that an author brings to their work. It may inform some of those factors, but what’s more interesting, from a creative point of view, is your overall worldview: the set of experiences that you, as a writer, translate into fiction. Gender is by no means the deciding, or even major, element in the translation of that mindset.

As a reader, and as simplistic as it sounds, all I want is to read a good book. That’s it. I don’t care if the author is an ancient Sumerian rabbit god with a lisp, as long as the story they tell moves me, involves me, and just maybe, leaves me looking at the world through a different lens. I’m old enough to have grown up whilst it was still relatively easy to find Leigh Brackett, CL Moore, Julian May and the likes on a shelf. And whilst it was—and remains—a blight on the industry that a significant percentage of writers feel they have to conceal their gender in order to find an audience, from the perspective of my young reader-self it meant that, as I grew up, I paid attention to the name on the cover rather than the identity of the author behind them. I’ve no doubt that gender plays a part in the publishing business, which would lead me down a very different rant indeed, but once a book actually reaches the bookshelf, the gender of the author becomes a non-issue for me.

Ultimately, if the gender of the author is the sole reason you pick up a book—or worse, the reason you don’t—then you may be missing the fucking point a wee bit. Is my experience of, say, a George Eliot novel lessened because I might learn that Oor George was a woman? Could I be that simplistic a creature? And if I am, what the fuck do I do if someone hands me a Caitlin Kiernan book, or a Poppy Brite?

A book is a doorway to a shared experience, and if you’re lucky, an experience that you not only haven’t had before but could not conceive of having. If reading that book leads you to seek out information about the author, and if learning about their lives enriches your reading experience, then fantastic. But the book itself is the gift. The story within is the sole point of contact through which we, as readers, have the right to critique and analyse the author’s motive. Anything else, unless directly communicated by the author, is conjecture. To take the immortal Trillian entirely out of context: anything you still can’t cope with is, therefore, your own problem.

As an author, though, as an author: that’s a different bucket of cows. The truth is, at least within our beloved little genre, that SF remains the province of a largely masculine way of thinking, and what’s worse; it’s a masculine way of thinking that even Tony Abbott might occasionally find old-fashioned and bigoted. It is undeniably a struggle to pass a truly feminine, or transgendered, worldview through the gatekeepers of most magazines and publishers. From an editing point of view—particularly in the magazine field—we’re set up for the quick fix. It’s easier to filter for a muscular, action-driven narrative that responds well to a first reading than it is to reward a subtle, emotionally-shaded, character-driven narrative that needs two or three readings to fully unfold. To split such stories directly down that divide as typically male or female is, of course, a gross simplification in itself, but as Westerners we create a societal culture that demands women define themselves as emotional beings, and then create a genre infrastructure that makes it difficult to sell emotionally subtle stories. Is it any wonder that female authors who have the greatest success writing Spec-style novels have a tendency to either do it outside the genre or loudly disassociate themselves from it?

Of course, all comments can be filtered through my happy life as a fat, middle-class white man, and disregarded as necessary.

Q: And here’s the fun question. If you could book a trip on a time machine, where and when would you go, and why?

I’m having a hard time not hearing Kryten right now: “If I could go anywhere, absolutely anywhere at all in time, I think I’d probably choose to go back to a week last Tuesday… I did all the laundry, and then we watched TV. Wow, we won’t see the like of THOSE sorts of days again.” 🙂

Dinosaurs. It’s got to be dinosaurs. Because, well… dinosaurs!

Giveaway Question: “If you could go anywhere after you die, where would it be?”

Catch up with Lee on Facebook

Catch up with Lee on Goodreads

Catch up with Lee on Google+

Follow Lee on Twitter @leebattersby

Catch up with Lee on Linkedin

Lee’s Blog

Filed under Australian Writers, Book Giveaway, creativity, Dark Urban Fantasy, Fantasy books, Gender Issues, Publishing Industry, Tips for Developing Artists

Tagged as Angry Robot, Book Giveaway, Fantasy books, Lee Battersby, The Corpse Rat King, Writing craft

July 21, 2012 · 9:34 am

I have been featuring fantastic female fantasy authors (see disclaimer) but this has morphed into interesting people in the speculative fiction world. Today I’ve invited the talented Helen Lowe to drop by.

Watch out for the give-away question at the end of the interview.

Q: First of all congratulations on The Heir of Night (The Wall of Night series) winning the David Gemmell Morningstar Award. (For a full list of Helen’s awards see here). But you’re not new to winning awards. Your work has twice won the prestigious Sir Julius Vogel Award and your first win was in 2003 with a poem. Rain Wild Magic won the “previously unpublished” category of the Robbie Burns National Poetry Competition. Do you think winning awards helps writers reach readers?

Helen: Rowena, thank you regarding the Morningstar Award. Getting the news that The Heir of Night had won was quite a buzz, especially since I was “pretty sure” that it was the first Southern Hemisphere-authored book, and I was the first female writer to have won in either of the two Gemmell Award book categories. (I have since confirmed that this is in fact the case.) So it was nice to feel that The Heir of Night had managed to carry the flag through on both those fronts.

Helen: Rowena, thank you regarding the Morningstar Award. Getting the news that The Heir of Night had won was quite a buzz, especially since I was “pretty sure” that it was the first Southern Hemisphere-authored book, and I was the first female writer to have won in either of the two Gemmell Award book categories. (I have since confirmed that this is in fact the case.) So it was nice to feel that The Heir of Night had managed to carry the flag through on both those fronts.

In terms of what difference winning awards makes, I don’t really know, to be honest. The Booker and Orange Prizes seem to get a fair bit of attention, both from the media and book shops, but my impression is that most other awards don’t. So I’m really “not sure” in terms of reaching out to a wider readership beyond those who are already savvy to the awards.

Q: The second book in The Wall of Night series, is The Gathering of the Lost. I see you use the word series, rather than trilogy. Does this mean that each book is self contained and you plan to write one a year (or more?).

Helen: The Wall of Night series is actually a quartet, but pretty much I am using the terms ‘quartet’ and ‘series’ interchangeably… In fact The Wall of Night (series or quartet) is one story told in four parts, rather than four self-contained stories – in much the same way, I think, that The Lord of the Rings is one story told in three parts. Having said that, each of the four parts of The Wall of Night story has a slightly different focus, as well as being part of a continuing arc, so I believe that may give each book a distinct character.

Q: You’ve been awarded the Ursula Bethell/Creative New Zealand Residency in Creative Writing 2012, University of Canterbury. This lasts from January to June. What exactly does it entail? Do you write madly for six months? Do you teach as well?

Helen: The main idea is that I write madly for six months, which is what I have been doing – and get paid to do so, which as other writers out there will know is a pretty amazing feeling! There is no specific teaching requirement, but I have run three sessions for creative writing students focusing on my practical experience of “being a writer.” I will also do a seminar for the College of Arts’ scholarship students before I complete my term.

Q: Thornspell is your retelling of Sleeping Beauty from the prince’s point of view. What intrigued you about the prince’s side of the story?

Helen: The idea for the story first came to me when I was at a performance of Tchaikovsky’s ‘Sleeping Beauty’ ballet. I recall the moment when the prince first leapt onto the stage and I sat up in my seat and thought: “What about the prince? What’s his story?” The main character of Sigismund (the prince), the world, and the central thrust of the story all flashed into my head in that instant. But I think the main ‘hook’ was that first moment of realising that no one had ever told the prince’s story before, that he is mostly a deus ex machina to the traditional tale.

Helen: The idea for the story first came to me when I was at a performance of Tchaikovsky’s ‘Sleeping Beauty’ ballet. I recall the moment when the prince first leapt onto the stage and I sat up in my seat and thought: “What about the prince? What’s his story?” The main character of Sigismund (the prince), the world, and the central thrust of the story all flashed into my head in that instant. But I think the main ‘hook’ was that first moment of realising that no one had ever told the prince’s story before, that he is mostly a deus ex machina to the traditional tale.

I subsequently learned that Orson Scott Card had written a novel, Enchantment, that is partly based on Sleeping Beauty and told from a male perspective – but it is tied in with several Russian folk stories and much less recognisably Sleeping Beauty, I feel.

Q: In an interview on the Pulse, you say the world of Thornspell ‘is loosely based on the Holy Roman Empire during the Renaissance / early Reformation period – not in terms of events, but in terms of cultural geography and technology, such as how people lived, clothes, weapons, tools, and learning. I think that helps to “ground” the story for the reader’. Are you a big fan of history? Do you travel to real places to get the feel of them and walk through restored castles?

Helen: Rowena,I love history and read non-fiction history as well as historical novels. And yes, I do love visiting cultural and historic heritage sites when I travel, and to date have visited castles and similar in Scandinavia, the United Kingdom and Japan. But while visiting sites can give you historical ‘flavour’, which is important, I also draw on primary and secondary accounts and research as required, which I feel can be just as important for authenticity. Another important element for me is the literature of the times, which helps give a feeling for what contemporary people thought and felt was important – for example works like the Anglo Saxon Beowulf, or the medieval Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, or going further back, the Greek tragedies, or The Iliad.

Q: Thornspell is a Young Adult book. Did you set out to write a YA story, it did it just develop this way?

Helen: You know, I really didn’t. I tend to just write the stories “as they come” – but having said that, the ‘shape’ of the story did come clear fairly quickly. I would say that by the end of the first chapter I knew that it was “Kid’s/YA.”

Q: I was prompted to start this series of interviews because there seems to be a perception in the US and the UK that fantasy is a bit of a boy’s club. Do you think there’s a difference in the way males and females write fantasy?

Q: I was prompted to start this series of interviews because there seems to be a perception in the US and the UK that fantasy is a bit of a boy’s club. Do you think there’s a difference in the way males and females write fantasy?

Helen: If that is so, regarding the boys’ club perception, then I have to say I believe it is a completely false premise. In my experience, just as many women read Fantasy (and Science Fiction) as men, and what most men and women I know are reading overlaps to at least 80% – maybe even 90%.

In terms of my judgement as to whether there is a difference between the way women and men write Fantasy… I have never really analysed this so I have to go off ‘what I personally read and like’ and my feeling is that I can’t point to any substantive differences… For example, I love richly written, High Romantic Fantasy and both Patricia McKillip and Guy Gavriel Kay equally tick that box. I also like intricately plotted works that twist and turn, but can I pick between CJ Cherryh and Patrick Rothfuss? For character-driven storytelling: Daniel Abraham or Ursula K Le Guin? For adventurous storytelling: Barbara Hambly or Tim Powers? Even with gritty realism, sure there’s George RR Martin, but there is also Robin Hobb with her “Assassin” series. And although one may point to China Miéville for sheer imagination, the same applies to Elizabeth Knox with her “Dreamhunter / Dreamquake” duology.

Thinking as I go along here, if there is one difference that I might possibly point to – and without doing an exhaustive survey I can’t be sure – I suspect female authors “might” be found to use the first person point of view more. But it’s by no means an exclusive preserve!

Q: Following on from that, does the gender of the writer change your expectations when you pick up their book?

Q: Following on from that, does the gender of the writer change your expectations when you pick up their book?

Helen: No, absolutely not. I make my ad hoc reading choices (as opposed to books sent to me for review/interview) on the basis of three criteria: i) does the cover speak to me ‘across a crowded bookshop’ and draw me in? ii) Does the back cover blurb appeal? iii) When I read the first few paragraphs to pages, am I hooked enough to either buy the book or check it out of the library (depending on my locale at the time)? And that’s it. I pay very little regard to who the author is (except of course for when I’m looking for the ‘next’ book by an author I already follow) or to “quotes” by other writers or reviewers.

In terms of prejudging a book by the sex of the author, I really do think that’s a fairly foolish approach given the number of authors who write under pseudonyms. And even if I had been inclined that way, I think discovering that one of my favourite authors of “women’s historical romantic fiction” when I was a teen, Madeleine Brent, was in fact a man, would have cured me of it!

Q: And here’s the fun question. If you could book a trip on a time machine, where and when would you go, and why?

Helen: That’s an interesting question… You know, I think I might try for something like five hundred years in the future, just to see how we’ve evolved – whether we’ve managed to turn around what appears to be our current desire as a species to ‘trash’ our own planet, which in universe terms does appear to be something of an ark. And if so, how we’ve done it. As well as whether we have managed to get off-planet in any significant way. In other words, that good old spec-fic fall back: I want to check out the space travel!

Give-away Question: Helen: OK, given we’ve talked about The Heir of Night winning the Gemmell Morningstar Award, I have a copy of the book to give away, to be drawn from commenters who respond to this question:

Give-away Question: Helen: OK, given we’ve talked about The Heir of Night winning the Gemmell Morningstar Award, I have a copy of the book to give away, to be drawn from commenters who respond to this question:

On your voyage to Mars, what three Fantasy novels would you absolutely not be without – and why?

Follow Helen on Twitter: @helenl0we

See Helen’s Blog

Catch up with Helen on GoodReads

Listen to the SF Signal Podcast with Helen

Filed under Australian Writers, Awards, Book Giveaway, creativity, Fantasy books, Female Fantasy Authors, Gender Issues, Nourish the Writer, Writers and Redearch, Young Adult Books

Tagged as David Gemmell Morningstar Award, Helen Lowe, The Gathering of the Lost, The Heir of Night, Thornespell

July 18, 2012 · 8:35 am

Late in June, I placed the seventh novel bearing my name onto the bookcase in my living room. A few days later, a reporter from my local newspaper came by, took a photo of me standing in front of the bookcase, and asked a question that I should be a lot better at answering by now. What inspired you?

Late in June, I placed the seventh novel bearing my name onto the bookcase in my living room. A few days later, a reporter from my local newspaper came by, took a photo of me standing in front of the bookcase, and asked a question that I should be a lot better at answering by now. What inspired you?

The novel in question is Hush, the second book in my Dragon Apocalypse series from Solaris Books. I was tempted to explain my inspiration on most crass level, explaining that I wrote it to make money! I signed a contract with Solaris to write them three novels in exchange for some dough. I like to keep keep my promises.

But, there are lots of ways to make money. And, a nearly infinite number of possible books to write. So why Hush?

My second inspiration for Hush was to write a book unlike anything else I’d ever tackled before. This was a tough goal. As the second book of a series, Hush featured the same protagonist, the same narrator, and the same fictional universe as Greatshadow. The first book built up to a big fight with a dragon; the second book builds to a big fight with a couple of dragons.

Knowing that I was constrained by these structural similarities, I decided to keep things fresh by writing way, way outside my comfort zone. For Hush, I decided that reality was a crutch for those who can’t handle fantasy and decided that, if I were going to write in a fantasy universe, I’d write in a world defined by myth rather than bland and neutral laws of physics. In our world, the sun is a giant ball of gas that appears to cross our sky because our planet spins. In the world of Hush, the sun is a big-ass dragon living inside a giant, glowing pearl that sails across the blue waters of the Great Sea Above. At night, when the dragon rests, the dark sea begins to freeze. The stars are merely ice floes drifting in the currents of the ocean overhead.

Knowing that I was constrained by these structural similarities, I decided to keep things fresh by writing way, way outside my comfort zone. For Hush, I decided that reality was a crutch for those who can’t handle fantasy and decided that, if I were going to write in a fantasy universe, I’d write in a world defined by myth rather than bland and neutral laws of physics. In our world, the sun is a giant ball of gas that appears to cross our sky because our planet spins. In the world of Hush, the sun is a big-ass dragon living inside a giant, glowing pearl that sails across the blue waters of the Great Sea Above. At night, when the dragon rests, the dark sea begins to freeze. The stars are merely ice floes drifting in the currents of the ocean overhead.

The sun-dragon, Glorious, makes his journey across the heavens on a regular schedule because he’s something of an obsessive-compulsive. He was born into a world where the sun was an untamed thing that would drift across the sky at random intervals. There was no such thing as time. Glorious looked at the chaotic world that surrounded him, a world lacking predictable patterns of night and day and seasons, and thought that it would much easier to organize his thoughts if the movements of the sun could be made to follow a schedule. So, he flew from the material world to the Great Sea Above where he took up residence inside the pearl, steering it onto a predictable path and pace to satisfy his longing for order. In doing so, he accidentally created human civilization, since the ape-like creatures that once hunted and gathered in the timeless world discovered that, in a world with set day lengths and predictable seasons, it was easier to grow food than to hunt for it.

Alas, one dragon who wasn’t happy about Glorious flying off to live in the sky was Hush, who was deeply in love. Her affection for Glorious was unrequited, however, and when he abandoned the world her heart shattered. Bitter cold filled the void where her heart had once been, and she became the primal dragon of cold. Each year, she grows angry with Glorious as he warms the earth to the point that nearly all ice begins to melt. In her wrath, she begins to chase the sun as he crosses the sky, leading to shorter and colder days, weakening Glorious to the point that, in the northern realms, he disappears from the sky completely. With her wrath abated for the moment, Hush returns to her abode to rest, allowing Glorious to timidly return to sky, regaining his strength until it’s once again summer, and Hush’s hatred once more drives her to pursue him.

I was inspired to create this myth by the very roots of fantasy, the various mythologies—Greek, Norse, Egyptian, Asian—that form the foundations of our shared literature and also much of our shared morality. From our modern perspective, the material world may be understandable, but it’s under no obligation to make sense or have meaning. There’s not a lot of moral knowledge to be gained from knowing that the sun and stars are distant balls of hot gas. The idea that the heavens were the abode of gods, and that we might learn from their stories, now seems quaint. But, these myths continue to resonate on an emotional level. There’s something deeply satisfying about looking at a night sky and thinking of it as a canvas for sagas of love and betrayal, cowardice and courage. I’m hoping to capture a bit of this mythic grandeur in my tale of dueling dragons and the humans swept up in their battles.

Why do myths have such a hold on my imagination? Remember that bookcase I was standing in front of? If my novels were the only books it held, the shelves would be pretty empty. Instead, they’re packed, with Poe and Pratchett, Bullfinch and Burroughs, Sagan and Segar. While the middle shelves are full of hardcovers, the highest shelf I’ve reserved for old, dusty paperbacks, many rescued from my grandfather’s porch. He was a voracious reader who fed his appetites by scouring thrift stores and yard sales and buying paperbacks for pennies. His collection spilled out of his house and onto his porch, where I would spend much of my childhood digging among these yellowed pages looking for science fiction and fantasy novels.

It was the beginning of a lifelong love of words. It’s fun to see my books in bookstores, but some of my best experiences as an author have come when I discover used copies of my books in second hand stores. I remember the first time I found a copy of Bitterwood for sale in a thrift store, with a broken spine and dog-eared pages, waiting for some cheap but voracious reader to pick it up for a couple of quarters. There’s nothing wrong with loving books as objects, collecting hard covers still in their original jackets for prominent display in your living room, a monument to a work of literature that was important to you. But, for me, the most beautiful books have torn covers and browning paper, worn from having been read and reread by multiple readers. The pages may be half way to dust, but the words lived for a moment, at least, in someone’s memory.

It was the beginning of a lifelong love of words. It’s fun to see my books in bookstores, but some of my best experiences as an author have come when I discover used copies of my books in second hand stores. I remember the first time I found a copy of Bitterwood for sale in a thrift store, with a broken spine and dog-eared pages, waiting for some cheap but voracious reader to pick it up for a couple of quarters. There’s nothing wrong with loving books as objects, collecting hard covers still in their original jackets for prominent display in your living room, a monument to a work of literature that was important to you. But, for me, the most beautiful books have torn covers and browning paper, worn from having been read and reread by multiple readers. The pages may be half way to dust, but the words lived for a moment, at least, in someone’s memory.

And ultimately, that’s my inspiration for writing books. Seeing them in bookstores is fine. But, I still dream that, one day, some bookish kid might be digging through a stack of dusty paperbacks on his grandfather’s porch and find a book of mine, and bring the words inside to life once more.

James is giving away a copy of Hush.

James is giving away a copy of Hush.

What is your favourite Greek Myth

Filed under Book Giveaway, creativity, Nourish the Writer, Tips for Developing Writers

Tagged as Bitterwood, Book Giveaway, Dragon Apocalypse, Fantasy books, GreatShadow, Hush, inspiration, James Maxey, Writing craft

July 14, 2012 · 11:29 am

I’m expanding my series featuring fantastic authors to include fantastically creative people across the different mediums, which is why I’ve invited the talented Queenie Chan to drop by.

There are links to give-aways sprinkled throughout the interview.

Q: In the Eighties I lived in Melbourne and knew a bunch of comic artists. One of the things I noticed was that they would be obsessed with art work, the look, the over-all layout of the page, but story would fall by the wayside. On your website you say: ‘After all, the essence of manga is not so much the art, but the story-telling, themes and pacing. These three are what you should concentrate on when trying to tell a story — any story, not just manga.’ Have you always been fascinated by story? Did your parents read to you? When you saw a movie, did you imagine what happened to the characters afterwards?

Oh, that sounds real interesting! You sound like you met a lot of interesting people when you lived in Melbourne (I must say, I did too when I lived there for a year). Anyway, you’re right about the many different camps of people who read graphic novels – some are all about the art, others are all about the story, while yet more believe in a combination of both. Personally, I’ve always felt that story is more important than art – a story can’t be expressed properly if the art is inadequate, but I also have seen a lot of well-drawn manga/comics that are dull and boring despite beautiful, realistic renderings. I still feel that to work in any storytelling medium (which comics is), your first duty is to engage the reader’s attention in whatever the purpose of the medium is for, so if it’s comics, it should be story.

Oh, that sounds real interesting! You sound like you met a lot of interesting people when you lived in Melbourne (I must say, I did too when I lived there for a year). Anyway, you’re right about the many different camps of people who read graphic novels – some are all about the art, others are all about the story, while yet more believe in a combination of both. Personally, I’ve always felt that story is more important than art – a story can’t be expressed properly if the art is inadequate, but I also have seen a lot of well-drawn manga/comics that are dull and boring despite beautiful, realistic renderings. I still feel that to work in any storytelling medium (which comics is), your first duty is to engage the reader’s attention in whatever the purpose of the medium is for, so if it’s comics, it should be story.

So yes, I’ve always been more fascinated by story, and as you said, I like to imagine the continuation of stories after they’ve “officially” finished. My parents encouraged me to read as a child, but they never read to me much (neither read fiction, to be honest), and so I got my fix from a variety of different sources – books, movies, TV series, cartoons, manga and video games. Even as a child, I was always writing fan-fiction in my head based on my favourite TV shows.

Q: You say you plot the story, concentrating on the beginning and end and often let the middle take care of itself. And that: ‘In longer stories … there is time to set the characters free in the world you’ve created, and watching them interact with each other and with the environment. If your characters are well-constructed, then they would behave accordingly, and sometimes in ways completely unexpected to you.’ At this stage are you still brainstorming the story flow in a sentence or two, or do you actually start to draw and find the characters doing unexpected things?

Since I’m a comic book writer/artist, the way I work is quite different to prose authors. I’m not saying I’m representative of comic book writers or artists in general, but most people who work in the comic medium are often constrained by the number of pages available. So in my case, the first thing I do when brainstorming is to figure out how many pages a story can be, because if a story becomes too long, it may be impossible to draw (since it will be impossible to finish).

Since I’m a comic book writer/artist, the way I work is quite different to prose authors. I’m not saying I’m representative of comic book writers or artists in general, but most people who work in the comic medium are often constrained by the number of pages available. So in my case, the first thing I do when brainstorming is to figure out how many pages a story can be, because if a story becomes too long, it may be impossible to draw (since it will be impossible to finish).

With prose, you can always add paragraphs or sentences and rewrite things if you want, but unfortunately with comics, once you’ve set something down on paper, it can be very hard to change. You can’t add an extra two panels to page 26 of your page 170 book (so far) if you want to – it will mess up the panel flows for the rest of the book. Because of this, my brainstorming usually involves writing down what happens on page 1, then what happens on page 2, and continuing by making a page-by-page summary of what happens on each page.

This part isn’t hard, but sticking to it isn’t always easy. Things always change when you go from prose to images, so you have to accommodate having to insert extra pages in when you start drawing the comic. Other times you’ll have to shorten scenes or extend them, so these days, I always make sure I have a good “feel” of the story in my head before I draw anything. As I said, the longer your story, the more freedom you have in letting your characters have their character moments. You may find a scene play out different as you draw it than you originally imagined, but the overall arc of the story shouldn’t deviate from the plan too much.

Q: You say you consider yourself: ‘… a Citizen of The World.’ You were born in Hong Kong and came to Australia when you were six. Did you live in a multicultural suburb where you mixed with people from a lot of different backgrounds or was this interest in other societies just something that you uncovered as you came across books and movies from other cultures?

I grew up in a very multi-cultural suburb alright – I went to school with all sorts of interesting people and it was always lovely to learn about other cultures! I was always very interested in travelling, and not necessarily to other Anglophone cultures. As a child, I wanted to go to Africa, to the Middle East and to India, because I thought of these places as exotic, and with a long history.

I grew up in a very multi-cultural suburb alright – I went to school with all sorts of interesting people and it was always lovely to learn about other cultures! I was always very interested in travelling, and not necessarily to other Anglophone cultures. As a child, I wanted to go to Africa, to the Middle East and to India, because I thought of these places as exotic, and with a long history.

I think being a history buff helps a lot too. I read a fair amount about Ancient History, and it’s always been a kind of dream for me to visit those historic places that I’ve read so much about.

Q: You say: ‘The reason why I’m so interested in interlocking story threads has a lot to do with my interest in human nature, sociology and anthropology. One of the things I find infinitely fascinating about genre-based story-telling in general is the environment the story is set in, and how that influences the character’s morals, values and actions.’ This is where I come from when writing my own books. I like to put my characters in situations that make them confront what they believe. You’ve made me want to run out and buy some of your books now. Was there a particular writer/movie director/artist whose mastery of character and setting made you think, Wow, that is what I’d like to do, but in my own way?

Ah, nice to know we share that point-of-view in common! I think fantasy can get a bad rep amongst some circles, because people tend to think they know what fantasy is without having read any of it (D&D, girls in metal bikinis swinging swords at orcs). The truth is, fantasy is just anything that isn’t set in this world, but set in a different world; a world which has social conventions similar to our own. What better way is there to explore human nature, without all the political, racial, cultural and historical baggage that each one of us accumulates in this world, just by virtue of living in it? As you said, putting your characters in situations that make them confront their beliefs is what people in this world do every day, just as they do in the worlds you create in your novels.

Ah, nice to know we share that point-of-view in common! I think fantasy can get a bad rep amongst some circles, because people tend to think they know what fantasy is without having read any of it (D&D, girls in metal bikinis swinging swords at orcs). The truth is, fantasy is just anything that isn’t set in this world, but set in a different world; a world which has social conventions similar to our own. What better way is there to explore human nature, without all the political, racial, cultural and historical baggage that each one of us accumulates in this world, just by virtue of living in it? As you said, putting your characters in situations that make them confront their beliefs is what people in this world do every day, just as they do in the worlds you create in your novels.

As for people who have inspired me… there’s been far too many to list. I can point out one man in particular who set me on my path – Tezuka Osamu, the creator of Astro Boy. He was a thoroughly-entertaining manga artist, but also a great humanist, and I encountered his series Black Jack at a particular time in my life (I was 15) which left a deep impression on me. Black Jack is about a rogue doctor who charges exorbitant fees for his services, but he’s also a very good doctor who understands that some people have illnesses that have nothing to do with the physical. The ethical questions that crop up in that manga is quite interesting.

Q: From reading the blurb about The Dreaming it seems to have the feel of the movie Picnic at Hanging Rock, which had a lyrical dreamlike quality about it, and to also be a modern take on the Gothic Romance Literature. Are these two sources which might have influenced you subconsciously as you were creating this story?

Picnic at Hanging Rock was definitely the biggest inspiration for The Dreaming, and you’re right about the gothic literature influences. Rebecca by Daphne DuMaurier was the other big influence, as were movies like Rosemary’s Baby. The visual aspect was quite important for me (namely the way the school looked), but I think I wanted to create a more modern, “haunted-school” take on the whole Picnic at Hanging Rock mythos, so the story ended up bearing hardly any resemblance to any of these three books/movies. Which is a good thing. Even if you can name all your influences, it’s a pleasure to know that what you created is unique in its own way.

By the way, I have the first 2 volumes (of 3) of The Dreaming online as a free webcomic.

Q: Your chapter dividers in The Dreaming remind me a little of the black & white work of Arthur Rackham and perhaps Art Nouveau (Mucha). Do you have heaps of books on art?

Actually, I don’t have many artbooks, especially compared to other comic book artists. I’m not really big on art at all. As I mentioned before, I’m more interested in story-telling than I am in art, so people are often aghast when it turns out that I haven’t heard of [insert name of famous illustrator here]. It’s assumed that all people who draw must be big fans of the art world, but unfortunately… I’m not.

I really do like Mucha’s art style, though it wasn’t something I’ve discovered until recently. And while I love what I’ve seen of Arthur Rackham’s artwork (google images, yay!), I actually think that the chapter divider art for “The Dreaming” looks more like some of Gustav Klimt’s line artwork (that I randomly saw in a book somewhere). I must say that I wasn’t influenced by any particular artist when I drew those chapter dividers – Klimt’s work was something I encountered afterwards.

Q: With the Odd Thomas Series (stories originally by Dean Koontz), did Koontz see your work and ask you to illustrate his stories, or were the pair of you matched up by his/your publisher? (Reading your blog post about it, I see it was a little bit of both). So I’ll come up with another question. How is the movie project going?

Q: With the Odd Thomas Series (stories originally by Dean Koontz), did Koontz see your work and ask you to illustrate his stories, or were the pair of you matched up by his/your publisher? (Reading your blog post about it, I see it was a little bit of both). So I’ll come up with another question. How is the movie project going?

I believe we were matched up by our publisher Del Rey, though ofcourse, Dean has to like my work to begin with. I’m not sure what work he has seen of mine before we started working together, but we’ve had a good working relationship thus far, and it would be an honour if we did more books together. As of now, there’s three Odd Thomas books (In Odd We Trust, Odd Is On Our Side, and House of Odd), and I’m happy with how things are.

I believe the movie for Odd Thomas has been completed, and is looking for distribution. I don’t really know much about it, I’m afraid, since this is a project that is driven mostly by Dean. When it comes out, I’m sure all the Odd Thomas fans will run out to see it!

Q: A while ago at Supanova Kylie Chan pulled out some of your artwork and showed me. She’s so proud of the work you’re doing on Small Shen. Were you already one of Kylie’s readers? How did the two of you connect?

(Update Small Shen isi finished!)

Kylie approached me at GenCon a few years ago, and introduced herself and her novels. I didn’t really know of her or her work beforehand, but it was rare to see Chinese Fantasy be so successful, so I took an interest in her work. When I contacted Kylie, it turns out that she had a prequel to her series called Small Shen, and wanted to do something “graphic-novelly” with it. Since I relish the chance to draw some Chinese-style fantasy artwork, I decided to take on the project. That was how it all got off the ground!

It’s been fun working on this project, and I’m nearing the end. This has been a special book, because this is a book that mixes prose with comics, and is not a straight-forward graphic novel. It’s experimental, but so far it’s working out quite well, so I look forward to it coming out in Xmas 2012 from Harper Collins.

Here’s an interview Oz Comic Con did with Queenie about her Small Shen project with fantasy author, Kylie Chan (no relation), among other things.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=x7qNQ2ryrds]

Q: I was prompted to start this series of interviews because there seems to be a perception in the US and the UK that fantasy (in books) is a bit of a boy’s club. I’ve come across quite a bit of talk on the blogs recently about female comic artists and writers, and their lack of representation in large companies like DC. Have you come across this in your professional life?

I think this perception exists throughout a lot of pop culture. Even when talking about books, there’s a perception that sci-fi, horror, crime, thriller, literary, etc are all male-dominated. The only thing that is seen as exclusively female is probably chic-lit or romance – but even then, these books are packaged in such a female-oriented way that any chance of them appealing to a male audience is pretty much dead due to the deluge of pink covers. Meanwhile, there are a large number of successful female authors working across the genres, and there always has been.

I think this perception exists throughout a lot of pop culture. Even when talking about books, there’s a perception that sci-fi, horror, crime, thriller, literary, etc are all male-dominated. The only thing that is seen as exclusively female is probably chic-lit or romance – but even then, these books are packaged in such a female-oriented way that any chance of them appealing to a male audience is pretty much dead due to the deluge of pink covers. Meanwhile, there are a large number of successful female authors working across the genres, and there always has been.

Things are pretty much the same in the comics industry. While it’s true that companies like DC and Marvel dominate (and they are largely male-oriented), there are many female comic book artists out there who don’t work in superheroes, and are just doing their own thing. I’m one of them.

It’s true that there are a lot of assumptions being made by people outside the industry, though, and even inside the industry. Many comics industry blogs tend to cover only superheroes, and hardly any other kind of comic. If you’re going to focus on one small part of the comics industry, then yes, you’re going to get a skewed perception of gender.

Q: Following on from that, does the gender of the writer/artist change your expectations when you approach their work?

No, it doesn’t. I think a good writer is a good writer, and I don’t think the gender of the writer has any effect on the final work. Male and female writers may be interested in different things, or approach things from other angles, but a good story told well is exactly that, and all that’s left is accounting for differing tastes.

No, it doesn’t. I think a good writer is a good writer, and I don’t think the gender of the writer has any effect on the final work. Male and female writers may be interested in different things, or approach things from other angles, but a good story told well is exactly that, and all that’s left is accounting for differing tastes.

I think things are a little different for artists though. If you’re talking about artists who are paired up with writers, then it rests on the skill of the artist to tell the writer’s story effectively, and sometimes they don’t do that. However, that’s got nothing to do with gender though – it’s more to do with what genre that artist is used to working in. If an artist is flexible, they ought to know how to adapt themselves to different genres. If they don’t, and they believe that one-art-style-fits-all… then it can get a little awkward.

Q: And here’s the fun question. If you could book a trip on a time machine, where and when would you go, and why?

Ah, that’s a hard question. My answer can change each time someone asks me that question, depending on what I’m into at that particular point in time. Previously I said just after the meteor that destroyed the dinosaurs hit, so I can see the terrible global destruction that it must have caused (but I would probably die very quickly from it). But as of now, I may just take the easy route and travel to Ancient Egypt to watch them build the Pyramids and raise the Obelisk. I have a theory as to how they raised the Obelisk, and am wondering whether it checks out with history.

Queenie’s Blog.

Catch up with Queenie on Facebook

Filed under Australian Artists, Australian Writers, Book Giveaway, Comics/Graphic Novels, Conferences and Conventions, Conventions, creativity, Gender Issues, Genre, Publishing Industry, Story Arc, Tips for Developing Artists, Writers Working Across Mediums

Tagged as Astro Boy, Australian comic artists, Dean Koontz, Kylie Chan, Manga, Odd Thomas, Queenie Chan, Small Shen, The Dreaming

July 11, 2012 · 9:07 am

Bruce with Apple Blossom (1977)

I have been featuring fantastic female fantasy authors (see disclaimer) but this has morphed into interesting people in the speculative fiction world. Today I’ve invited the hardworking and insightful Bruce Gillespie to drop by.

I first met Bruce in 1976, when I went to Melbourne with Paul Collins to start an Indie Press publishing house. Bruce was living in Carlton with his cat Flodnap (and his cat’s cat, Julius) and had been editing fanzines for 8 years. By 1976, Bruce had been nominated for a Hugo three times, so despite being only 29, he was already one of the Grand Old Men of Australian SF Fandom.

Q: Your work had received three Hugo Nominations before you were 30. You have received total of 45 Ditmar Nominations and 19 wins, and The A Bertram Chandler Award in 2007, plus you were fan guest of honour at AussieCon 3, the World SF Convention in 1999, is there anything left that you would like to achieve?

A: Like any other fanzine editor or writer, I would actually like to win the Hugo Award for either Best Fanzine or Best Fan Writer! But that seems impossible these days, since even in 1999 and 2010, when the world convention was held in Australia, I could not gain enough votes to reach the nominations list.

A: Like any other fanzine editor or writer, I would actually like to win the Hugo Award for either Best Fanzine or Best Fan Writer! But that seems impossible these days, since even in 1999 and 2010, when the world convention was held in Australia, I could not gain enough votes to reach the nominations list.

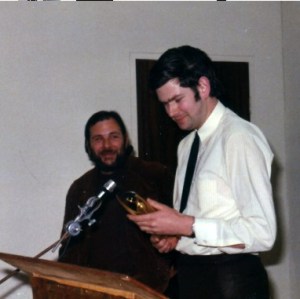

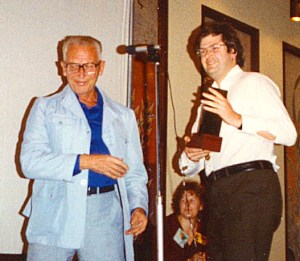

Bruce receives his first Ditmar from John Bangsund (1972)

However, in 2009 I was awarded the Best Fan Writer in the annual FAAN Awards, given by my peers, the fanzine writers and editors who attend the Corflu convention in America. I count that as a great honour, along with having received Australia’s two awards for lifetime achievement, the A. Bertram Chandler Award (as you mention) and the Peter MacNamara Award. In practical

terms, the greatest honour I’ve received was the Bring Bruce Bayside fan fund, which enabled me to return to America (for the Corflu and Potlatch conventions) for a month in 2005.

- The Gang (1967)

John Bangsund, Leigh Edmonds, Lee Harding, John Foyster, Tony Thomas, Merv Binns and Paul J Stevens

- The Gang (1967)

Q: In your 2012 snapshot interview you say: A fanzine is a minor artform, based on putting together a wide range of material from my favourite writers, plus response from letter writers from all over the world. The use of a computer limits the artform in some ways, but also offers design, editing and font possibilities that were impossible to access in the Good Old Days (pre 1990s) of using stencils and duplicators.’ You have been producing zines now since 1968, that’s 44 years. In that time you must have worked out what makes a good fanzine. If you could go back now to Bruce circa 1968, what advice would you give him?

A: I could have warned him not to use the typewriter with which I produced the first SF Commentary in 1969. It was a little Olivetti with a beautiful typewriter face — but unfortunately it would not cut a stencil properly. For a fanzine that was almost illegible, SF Commentary No 1 gained an enormous response from people around the world, including a letter from Philip K. Dick, my favourite SF writer.

A: I could have warned him not to use the typewriter with which I produced the first SF Commentary in 1969. It was a little Olivetti with a beautiful typewriter face — but unfortunately it would not cut a stencil properly. For a fanzine that was almost illegible, SF Commentary No 1 gained an enormous response from people around the world, including a letter from Philip K. Dick, my favourite SF writer.

But apart from that, how can you give advice to a 22-year-old, especially someone with far more energy than I have now? ‘Follow your nose?’ ‘Never give up?’ I knew then that no matter how people responded to my fanzines, that was what I should be doing. Nothing’s changed.

Bruce with Brian Aldiss at Stone henge (1974)

Q: In the same interview you said: ‘Of course, I can publish electronically, using PDF files, on Bill Burns’ wonderful efanzines.com, but I know that many people download such magazines and don’t read them with the attention they would devote to a magazine they received through the mail.’ I do most of my reading on-line, following science blogs, political activists and researching. Personally, I don’t feel that I give less attention to my on-line reading. What leads you to believe that an on-line magazine is valued less than a print magazine?

A: For someone of my generation, a paper document has real existence, and online documents don’t. I don’t really believe that the current electronic publications will be available or readable in twenty years, let alone forty, but I still own almost all the paper fanzines I’ve received since 1969. If I value anything I find Out There, I copy it into a Word file and print it. More to the point, many of my correspondents say that they reply to paper fanzines, and don’t respond to fanzines posted on efanzines.com. That’s if they even take the trouble to download.

The current situation is that I can no longer afford to print and post my fanzines, so I will be asking almost all my readers to download them. This will sharply reduce the number of letters of comment I receive, but it gives me much more freedom to publish much more often.

Q: You once said about Fandom: ‘Before I joined fandom I had almost no friends or anybody with whom I could share my interests. In fandom I found people who were not just another part of the mundane world, which I find stifling. During a weekend I spent at Lee Harding’s place in late 1967, I met for the first time many of the people who have had the most influence on my life, such as John Bangsund, Lee Harding, George Turner, John Foyster and Rob Gerrand.’ (See Bruce’s post about science fiction and fandom here). I must admit that it wasn’t until I came to Melbourne with Paul in 1976 that I met people I could talk to. I’d come from Brisbane where all people talked about was football and getting drunk (obviously I was moving in the wrong circles). In Melbourne fandom I met fascinating people who could hold stimulating conversations on all manner of topics. I felt like I’d come ‘home’. Nowadays with the WWW people can make contact with other like-minded people, but forty years ago it was much harder. SF fans were considered extremely odd. Can you give readers a glimpse of what it was like to be a fan in those days?

Melbourne Fandom in 1954

Back row: Merv Binns, and Dick Jenssen

Front row: Bob McCubbin, Bert Chandler and Race Mathews

A: At school, I had only two friends who read science fiction at all. Nobody else I knew read SF, although the SF magazines were much more widely available (in newsagents) than now. At university, no other students seemed interested. However, I did read in the Bulletin in 1966 that Melbourne had just held an SF convention. Charles Higham wrote what remains the fairest report any Australian journalist has ever offered of an SF convention. He made it sound very exciting. I also knew that the Melbourne SF Club held its meetings every Wednesday night in Somerset Place, which was behind McGill’s Newsagency in Elizabeth Street. McGill’s had the only good stock of science fiction in Melbourne, and I realised that this had something to do with the tall thin man who loomed behind the counter (who was, of course, Mervyn Binns, who has just been given the Infinity Award for his services to fandom). Every science fiction book sold in McGill’s included a little leaflet advertising the club. Also, McGill’s sold a magazine called Australian Science Fiction Review (ASFR). The quality of the reviews and articles in this magazine were staggeringly far ahead of those in the pro SF magazines, for both intellectual content and sparkling style. However, I knew I would never finish my degree if I became involved in fandom from 1965 to 1967. At the end of 1967 I wrote several articles on the works of Philip K. Dick and sent them to John Bangsund, the editor of ASFR. He rang me in December 1967 and suggested I visit his home in Ferntree Gully to meet the people who produced the magazine. This was the beginning of my career in fandom, for I met people who read what I read, talked about what interested me, and who were interested in what I had already written.

Bruce with Allan Sandercock (1971)

Q: You are a qualified school teacher and did teach for two years, but gave it up to produce fanzines and write about speculative fiction. You said: ‘My mundane career has never gone anywhere much, and I’ve often been nearly broke. But my career in fandom (as an editor), which has never made me any money, has led to most of the good things in my life.’ What do you think are essential traits an editor needs?

A: That’s not quite right. I gave up teaching because I was hopeless at it. I was very close to suicide at the end of 1970, but a friend prompted me to do what I would have thought unthinkable — resign. When I did this, the Department wanted to keep teachers, so I was offered a series of bribes to stay officially a teacher. The last of these was a position in the Publications Branch of the Department. In 1971 and 1972 I received a full on-the-job training in professional editing and journalism. I left in mid 1973 to go overseas, visiting fans all over America for four months and a month in Britain. When I returned I decided to try freelance book editing. I knew there was no editing work in SF in Australia, but my friend John Bangsund was making an intermittent living from freelancing, and there was plenty of work, especially in textbooks, in 1974.

The essential quality of an editor is to love correcting other people’s writing. You trawl through a book and can see how you can improve it. Many editors (especially my wife Elaine) are much better at it (are much more meticulous) than I am, but I’ve kept on working over the years, sometimes successfully (as during the twelve years I received guaranteed freelance work from Macmillan in Melbourne) and sometimes disastrously (such as at the end of 1976, when I was actually forced to take a part-time office job for a year or so). Elaine and I have learned to skate along from cheque to cheque, and sometimes those cheques are very thin on the ground.

Bruce Gillespie and Elaine Cochrane on their Wedding Day (1979)

Q: In 1979 along with Carey Handfield and Rob Gerrand, you were one of the founding editors of Norstrilia Press, which published Greg Egan’s first novel, among others. Was there are particular philosophy that the three of you developed when you started Nostrilia Press?

Dick Jenssen and Rob Gerrand (2005)

Bruce Gillespie and Carey Handfield (1975)

A: Like the other small presses of the time, including Cory & Collins and Hyland House, our aim was to publish material that no major publisher would touch. You might remember that during 1973, for instance, there were 17 novels of any genre published by all Australian publishers. Even after the Australia Council began its publishing program under the Whitlam Labor Government, most of the spate of new titles sprang from the small press enterprises, such as Outback Press.

Carey said that the aim of Norstrilia Press (named in honour of American writer Cordwainer Smith, who had a great love of Australia, and whose only novel was Norstrilia) was to return enough money to SF Commentary, my magazine, to keep it going. This never happened, of course, but our first book (1975) was a set of essays called Philip K. Dick: Electric Shepherd. All the material, which included essays by Stanislaw Lem and George Turner, came from SF Commentary.

Carey devised a complicated system by which individual fans invested in particular books that we published. Since eventually we had to provide a return on investment, we diversified quickly. (Our only other critical book was The Stellar Gauge, essays by the finest critics in the field, edited by Michael Tolley and Kirpal Singh in 1981).

Our second book was The Altered I, with stories and essays based on the Ursula Le Guin Writers Workshop of 1975 (held in association with Australia’s first world convention, Aussiecon 1).